Hated is a strong word - maybe just seriously disliked?

Regardless, they did not like me or my writing, and they definitely did not want me in their class. Neither did my professor.

Let me explain.

A Lucky Break

I’ve always needed to tell stories. First it was dirty jokes – I was the class clown and designated campfire joke teller. How the hell did 12-year-old me find so many dirty jokes? I was a sponge and sucked up everything I could, then turned around and told them to anyone who would listen.

And while I loved the tension and release of a good joke, I never understood any form or method for telling them. I just loved the microcosm a good joke creates. In less than two minutes: setup, turnaround, punchline. A good joke does a lot with very little.

In another life I’m a standup comedian, but for this reality, I went to college to learn to write. It is one of the most important and practical decisions I made when 17-year-old me decided: I want to write a lot and become really good at it – so I’ll study journalism.

This changed my life.

Back in the spring of 1991 (which coincidentally is in the middle of one of the greatest moments in rock music – more on that in a later post), I needed to sign up for an English class and so I did what everyone did before computer registration: I walked over to the English building, found the bulletin board with the posted classes, and looked at which ones still had space.

My dorm room looked out at the English building and whatever the timing was, one spring morning I realized signups had just opened and I should just get it done while I was still thinking of it. So I walked over there and found the bulletin board.

I remember standing before the board, a dozen or so English class signup sheets tacked in an orderly grid.) Another crazy anachronism is that my student ID was just my SSN, so we just put that piece of highly critical personal information EVERYWHERE. Sign-ups just required your name and SSN in the open spaces on the board.) Looking over the available classes, half of the classes were full already, and as I looked for a cool reading or writing class I found the jackpot: a 400-level (pre-graduate) Fiction Workshop with only 12 student capacity, of which 8 had already been taken. The single prerequisite was Fiction 101, which I had completed the previous year.

Perfect – I put my name down and left for the rest of my day.

I didn’t know this at the time, but I had just made a life-changing decision that I still can’t see the full impact of.

Imposter Syndrome is Real

At some point in kindergarten, I got on the wrong bus. There was an early bus and a late bus – I was in a double-sized class that was broken into an early and late schedule because the 70s – and I was a late bus kid but somehow one day I left class with all the early bus kids. Standing in line, all the kids around me – the big first and second graders – all of them telling me I’m in the wrong line and I’m just trying ignore them – I can still feel the anxiety rising up in me 50+ years later.

I wasn’t supposed to be there.

And then when I got on the bus, I realized those kids were right – I looked up and down the seats for a friendly face and found no one, but now I was on the bus and at least I got the route right. By the time I got to my stop my mom was there because the school had called her and let her know that I left early. So, she picked me up at my stop and I was a little rattled in the way a five-year-old can be when something weird and undefined has happened. It’s not a big deal - the whole thing was a mistake, and I wasn’t in trouble. I just needed to get on the later bus.

But that feeling of isolation and otherness still burns in me half a century later. Getting on the bus and having everyone stare at me, the message was distinct: you do not belong here. (This is a feeling I imagine non-white men feel much more frequently.)

Flash forward 15 or so years and now I was in college and sitting down in my first 401 Fiction Workshop with just 11 other students, and everyone is in quiet awe to be under the care and tutelage of our esteemed and award-winning professor Ehud Havazelet.

Now I know that Ehud is an award-winning writer but at that point I had no idea what I was getting into. And quickly everyone else at the table knew that as well.

As the introductions went around, everyone was asked to talk about one of their favorite books, and most of the titles I had never heard of. Maybe someone said Moby Dick or War and Peace to try and impress Ehud (not easy to do), but the stakes were raised significantly when I had no idea what to say and just blurted out, “Animal Farm.”

I was smart enough not to say, “The Hunt for Red October,” which I was reading at that time (classic Tom Clancy thriller). But I might as well said that because no one was impressed with this mandatory middle school reading.

It didn’t take me long to realize that everyone else in the class had already taken a class with Ehud and had some sort of literary aspirations that lined up with his award-winning style of literature. And over the first month of the class, I felt more and more detached from the class, just like I felt when I took the wrong bus home.

But let’s first discuss literary fiction versus genre fiction.

Imagine a group of early people, gathered around a fire, and a storyteller named Ott is describing their encounter with a particularly beautiful field of flowers, and the berries that lined the edge of the field, and how the thorns on the berry bush pricked their finger and reminded them that everything sweet must come with a price. And everyone around the fire nodded at the life-affirming details of Ott’s story. Good story Ott.

Then the hunter Ogg shows up with blood on their hands and everyone asks, “What happened?” and Ogg shares an encounter with a very angry sabretooth tiger, they describe the chase and the fighting and the blood, and suddenly no one cares about Ott and their beautiful berries. Ogg is now everyone’s favorite storyteller and all Ott has is their berries.

And ever since, literary fiction writers have hated genre writers and worked hard to keep them out of all the prestigious award ceremonies. They’ve labeled genre writers – and genre fiction as a whole – as hacky, unintelligent, and not worth the paper it’s written on.

When a genre writer shows up to a literary fiction workshop and innocently expects a seat in the circle, there is, as the kids say, organ rejection. That’s what it was like taking a graduate level class with 11 other aspiring literary fiction writers and me, just some weirdo from the street.

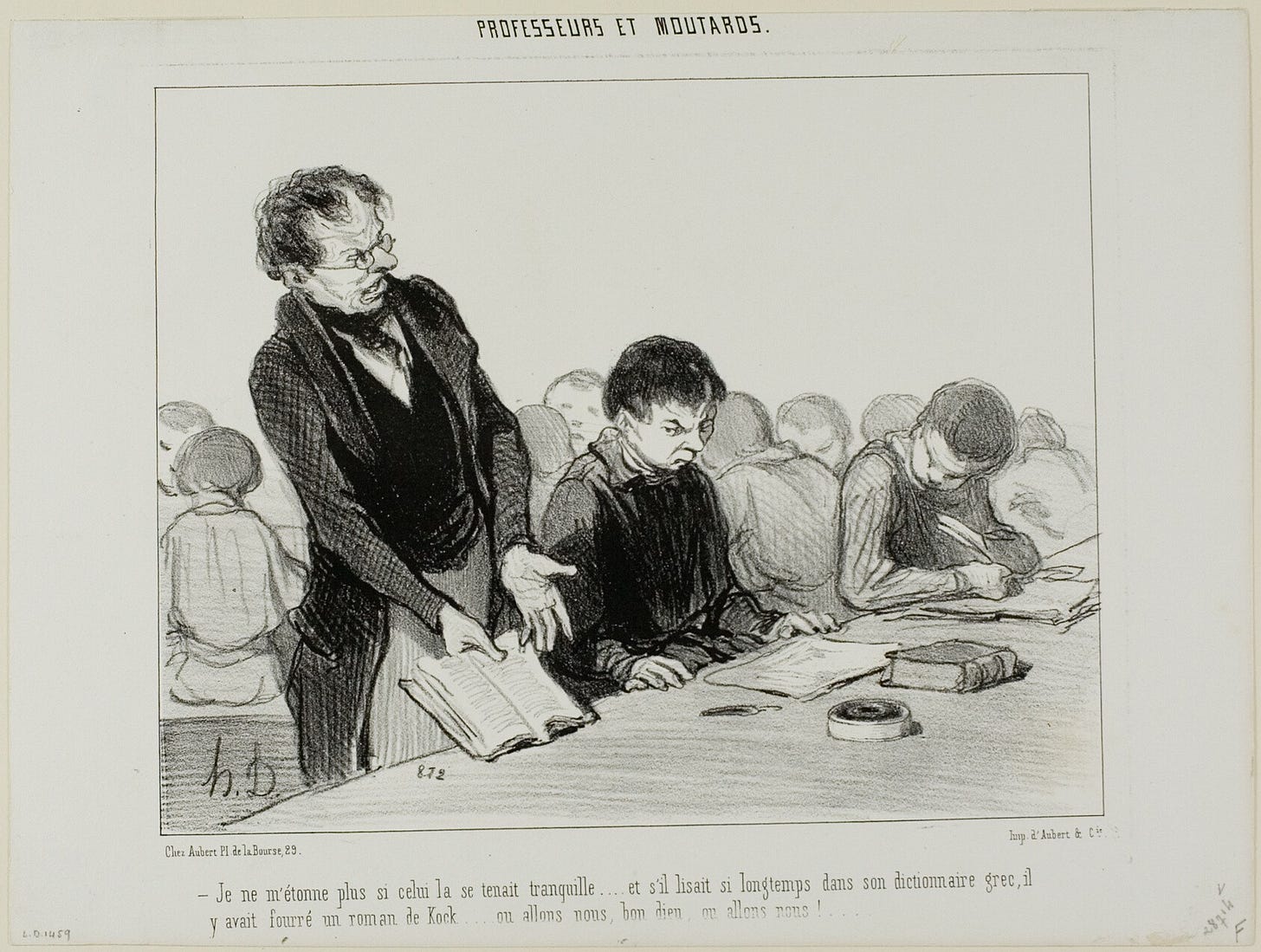

The class was very workshop-heavy, chairs pulled into a circle, where someone would share a piece and everyone would pick it apart. We were expected to write two 10–20-page short stories over the quarter, and workshop at least one of them with the group.

At this point in my writing career, I didn’t know what I wanted. What I could have really used was a more intermediate “how can we figure out what we like to write?” course, but I had skipped right from introduction to advanced and had no framework or perspective on what I liked or didn’t like.

(I also had, for much of my life, near-crippling ADHD that made sitting down and focusing for long stretches of time – like I’m literally doing writing this piece – impossible. Writing my way into a voice or rhythm was really, really difficult for me.)

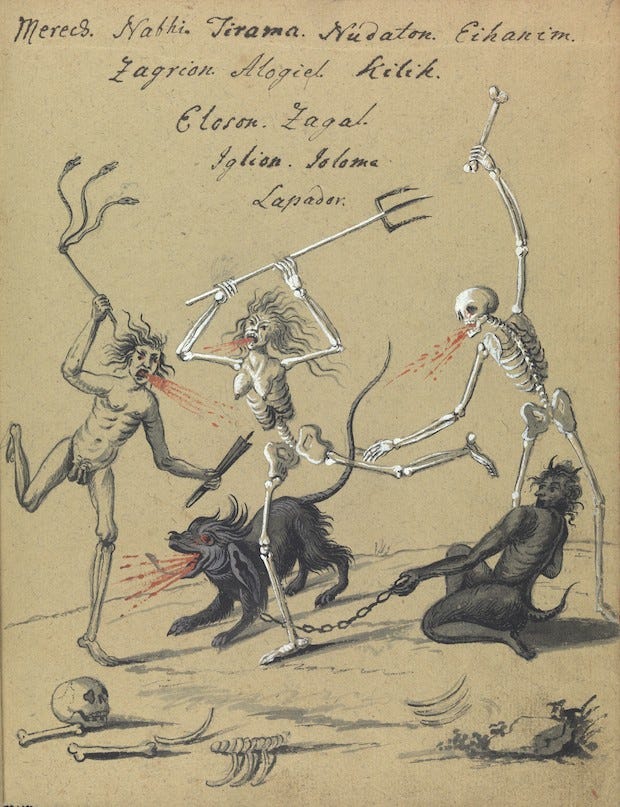

So, when it was my turn to share, I turned in a story that was clearly influenced by my then recent discovery of HP Lovecraft and my long-time love of Stephen King. I will give you the abbreviated version now.

A man returns home to his family’s cursed and dilapidated mansion by the sea; after leaving once he discovered his relatives were all part of a witch coven. Having returned, he now walked through the house and described all the crazy stuff he saw when he was last there as a teenager – the sex magick rites of course as well as the summoning rituals and blood sacrifices – and he thought about returning the house to its non-orgy days of glory.

He stood at the cliff-edge looking out at the sea and the opportunity it represented, and turned to find the butler behind him. The butler was the only person still around from the cursed family days, and the narrator trusted him, believed they could rebuild the legacy together. “Ah, Roger, I’m so glad you’re here. You can help me make things right again?”

“Yessir, I know what needs to be done,” said Roger with a weird smile and then pushed the man off the cliff to his death. “All is right.”

That was the story, but with an additional 12 pages of description. When my friend Doug read it, he said, “Well, you know I love it when the main character dies,” and that was it because he was being polite.

It’s not a good story but it’s okay for a 20-year-old ADHD-addled Californian with dreams of being the next Stephen King. I think it’s kind of silly and can definitely laugh at myself, which is the right response 35 years later.

But my classmates did not like it. At all.

Like, AT ALL AT ALL.

And, perhaps more importantly, they didn’t know what to make of it, or me really. Who was I to write such genre garbage? Had I learned nothing?

My story’s workshop could have been the final nail in my fiction writing career’s coffin, except that I didn’t have any serious emotional attachment to this particular piece. I think my classmates really wanted to make it clear that I should not be in the class and that I should never, ever write “fiction” again.

I remember the particular workshop because Ehud was absent and another professor took the workshop and whew – he was just confused. He didn’t know me at all and had no idea what my crazy, weird piece was about. Everyone else hated me, he just had no idea what to do with me.

The general feedback I received was that my story was a hacky retread of gothic horror and almost pornographic levels of vice and avarice, that there wasn’t a single redeeming quality to it, and that I had no idea what I was doing and should probably stop not only writing but even reading whatever it was that I was reading.

(The joke is on them clearly because I got this post from that story, so there’s your redeeming quality, la de dah.)

And while I didn’t take the feedback personally, I also didn’t know what it meant for me in the class. I can read a room, and it was clear that all my gut instincts that told me I was in the wrong place were right. I wasn’t proud of my piece but it had taken a lot of work and isn’t that what we’re really trying to do here?

When Ehud got back he called me to my office. We needed to talk.

Now that I’m in my 50s, one of my favorite mental exercises is thinking about people in my past and relating myself in my middle age to that person at whatever point they were in my life. I do it all the time with my dad – oh, here’s what my dad was like when I was his age – but I also do it with former bosses and co-workers who were older than me.

Sadly, Ehud died a decade ago at 60 years old, which is far too young. But when I took his class, he was only 35 or so, building a life in Oregon as a successful literary author and professor. He had successes and had successfully navigated academic politics to build this very special graduate level workshop where he could do quality work with students dedicated to the craft of fiction writing. He got his MFA from the Iowa Writers Workshop, which at the time was the most prestigious fiction program in the country. He was not fucking around.

And then here I come.

I wasn’t trolling him, which I think he suspected at some point. When I got to his office he asked, “do you even like my class?” He acknowledged that I was clearly into the class and curriculum – I attended every class and fully participated and even had good comments and criticisms.

But my story was not at all what he was looking for and it made him question if I even got what he was trying to do. And really, at least at that point, I had no idea what he was trying to do. In my memory, I can see him frustrated with me but also having the grace and patience to see that I was lost. And this wasn’t the Fiction 101 class, where the bar was much lower. He had to help me see the path he had laid down – for both of us, this was an important teaching moment.

Toward the end of the conversation, he steered his advice toward the practical. I needed to write something based on my emotional experiences. Not plot or genre driven. Something based on human experience. How I feel, what I experience, how the conflicts of life materialize in prose. I remember him advising, “Write about how you felt in when the class workshopped your story – I bet that was a really tough experience.”

Looking back, that is actually really great advice. But at the time, I just thought:

Uh, okay.

And so I did that and wrote something about walking around the neighborhood after a girl broke up with me, dwelling on my bent tie, a detail I remember him liking. And it was good enough to get a C on the essay and in the class. And I think we were both glad I was done with that whole thing.

Ehud was notoriously harsh on his students – he had high standards for himself and he expected the same from his students. Later I would meet a friend who had taken Ehud’s Fiction 101 class and we bonded over not writing the “right kind of fiction,” at least in Ehud’s mind. We had survived the same early traumas and shared our scars.

But in this memory exercise, for all of his strong opinions, he never told me not to write or that I was terrible. He put it back on me – What am I seeking? What is in my heart? What do I want from my writing?

These are questions from a really great teacher that, writing styles aside, can put a writer on the right path for the rest of their lives.

I can say now, definitively, that I am actively writing genre fiction and that it would not be something that Ehud would like. Or maybe he would. Sadly, he died ten years ago and I’ll never be able to ask him.

I would love to sit down with him now and talk about fiction. I have such a stronger perspective on writing and voice and craft now – I’ve written so much more and come to respect all types of writers and fiction, even if they don’t necessarily return the favor. And while I do not care that my classmates did not like me or my story, I am glad for this experience and perspective on what taking graduate level fiction classes in the early 90s meant for everyone involved.

But I do think Ehud and I are wholly aligned on how writing is a lifelong journey and creative pursuit, and that AI doesn’t really have anything to offer someone who has dedicated their lives to trying to get their story out on paper.

I would like to think that, decades later, Ehud and I could share a coffee and find a middle ground between us on how a writer needs to be both brave and quiet, focused and reckless, conformist and revolutionary. That we both want a world where writing is both an art and a craft, and that genre or not, an author’s true responsibility is to write from the heart and tell their own story, regardless of whatever the fiction market is buying that month.

On those things, I know we can agree.

I put some of the blame on your prof, famous writer though he may have been. That opening exercise — "what's your favorite book" — is a recipe for a room of insecure (not just you) undergraduates sitting in a room with a famous writer to show off and shame each other. Which is what happened, and a terrible way to start a course that — to work — is going to require a community of trust and care. No one thought about college that way in 1991 but what you experienced was *not* (just) about you.

Similarly, you didn't understand what he was trying to do. How could you have? Another feature of poorly/carelessly designed courses is you make the students figure out everything on their own. What would it have been like for you if Ehud on the first day had said "this is a course in which we are going to write X type of fiction. I know not all of you want to write that kind of fiction. Some of you want to write genre horror like Stephen King or thrillers likeTom Clancy. I'm not into that kind of writing but it's a big world and there should be a lot of different kinds of writing. But for this semester I'm going to require you to write X type of fiction. And this is going to be useful to your life as a writer, no matter what kind of fiction you want to write or end up writing, because writing X type of fiction teaches you A B and C about writing and those are worthwhile things to learn. If you don't even want to try that, this isn't the class for you, but I'm asking you to trust me that it will be worthwhile just to work on it for a semester."

Thank you for sharing such an insightful and vulnerable part of your life. I have definitely shared your sentiment of feeling being an outsider.